|

| Don't worry T-Rex, I hate them too. |

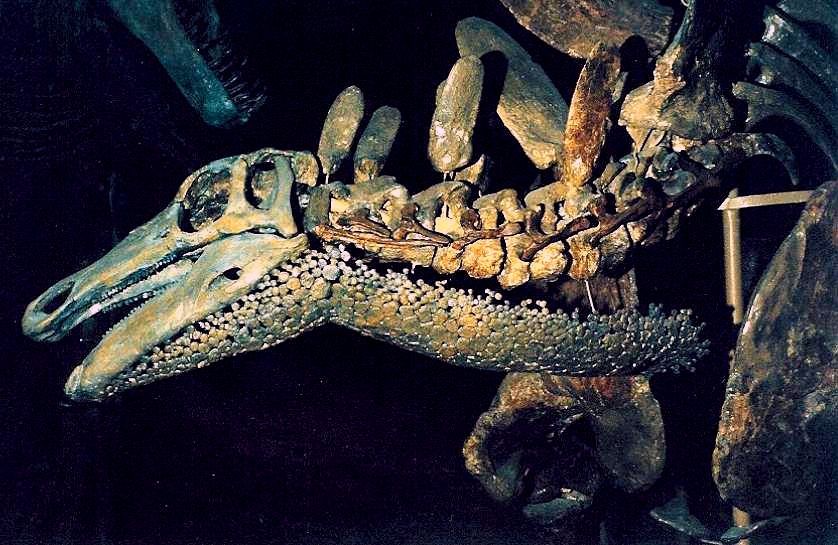

Tyrannosaurs had huge heads, terrifying jaws, and extremely powerful bodies, so it doesn't really make any sense that these predators have those puny little two-fingered arms now does it? Some have taken this as evidence of a loss of predatory lifestyle in the tyrannosaurid group, while many others find the small arms as being lost to compensate the enlarged jaws. Both, however, have their problems, and that's what my new Predator vs Scavenger topic is about! We will be reviewing the structure, musculature, evolution, ontogeny, and all the known possibilities for the strange arms of the tyrannosaurids to attempt and find out why tyrannosaurids evolved their tiny little appendages.

___________________________________________________________________________________

Biomechanics of the Tyrant's Tiny Limbs

When

Tyrannosaurus rex was first discovered in in the first few years of the 1900's, only the humerus (upper arm bone) was recovered, and the first mounted skeleton of T-rex in 1915 portrayed it with three fingers like those of

Allosaurus and most other theropods. However, a year earlier the forelimb of

Gorgosaurus was described and showed the typical two fingered hands characteristic of tyrannosaurids. It wasn't until 1989 that we had our first complete T-rex forelimbs, and proved just how short and tiny these arms were.

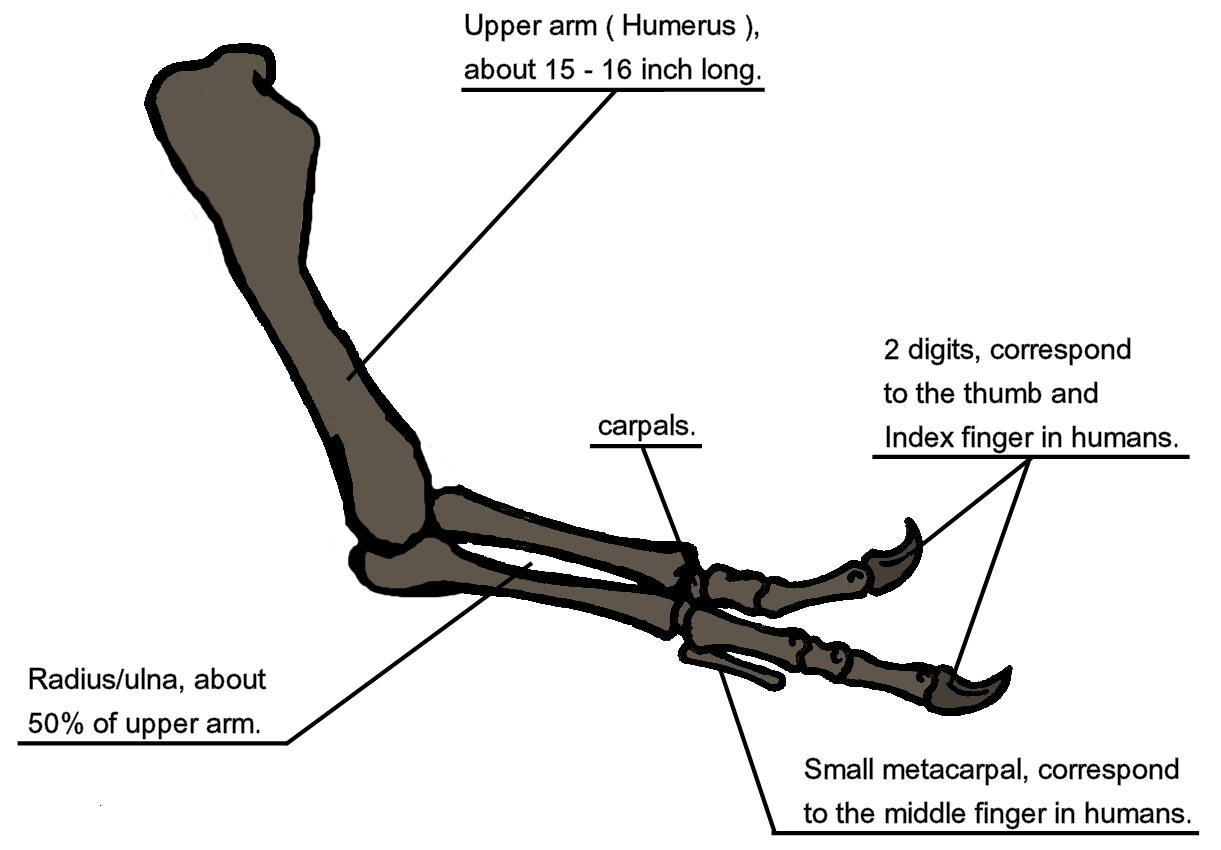

The arms were small relative to the animal's body size, only about as long as a average human's. The humerus of T-rex was roughly 15 - 16 inches long, and was made up of extremely thick cortical bone (a type of bone with very little openings and high density), making it able to withstand heavy loads. The radius and ulna (lower arm bones) were both only about 8 inches long, and weren't quite a strong as the humerus. The hands were made up of the two small carpal bones, one reduced metacarpal that represents the lost third finger, and two functional digits.

It's true these arms were tiny, but they certainly weren't vestigial or useless. Like I said, the arms were made up of thick bone, and was built to withstand strong forces. Their are also areas on the arms and the long shoulder blades for large muscle attachments. In fact the biceps of a full-grown Tyrannosaurus was capable of lifting over 400 pounds, not even counting the four other kinds of muscle present in the arm.

Even though the arm was particularly strong, it had a reduced range of motion, and was only capable of allowing 40 degrees of motion at the shoulder and 45 degrees at the elbow. Compared to humans this is very small range, but even other theropods such as carcharadontosaurids, allosaurids, and especially members of the maniraptora all have a range that greatly exceeds that of the tyrannosaurids.

___________________________________________________________________________________

Evolution and Ontogeny of the Puny Little Arms

The tyrannosaurs didn't always have their tiny arms though, early tyrannosaurs like Guanlong, Dilong, and the (really) recently discovered Yutyrannus all have arms that are either in the typical size range of most other theropods, or actually longer. It was only the later, larger tyrannosaurs that evolved their abnormally small forelimbs, though exactly when these tiny arms evolved in the first place remains unknown.

In 2010 the mystery was thought to have been solved by the discovery of Raptorex, which was thought to be a small tyrannosaur from the early cretaceous that had already evolved the two-fingered limbs. However, it was later studies on the specimen showed that Raptorex wasn't actually from the early cretaceous, but actually dated to the masstrichian stage of the late cretaceous. Not just that, but the remains are strikingly similar to known Tarbosaurus juveniles, and the specimen itself is already known to be immature. Many now consider Raptorex to be a nomen dubuim, and most likely represents a juvenile Tarbosaurus. Thus, the mystery as to where these stubby little arms emerged remains anonymous.

At the moment, the transitional morph is still yet to be found, but based on my knowledge of these tyrants, I personally believe the small arms probably evolved about 85 mya in either North America or Asia. Both places have early tyrannosaurids present, in Asia it was Alectrosaurus and in North America it was Appalachiosaurus. Sadly the front limbs of both species are unknown, so whether or not they had short arms of animals like Tyrannosaurus or long arms of creatures like Yutyrannus is still a mystery. All the tyrannosaurids from 80 mya onwards had puny little two- fingered digits.

However, it does seem that at least one tyrannosaurid "bucked the trend" a bit when it came to the puny arms. Daspletosaurus torosus had the longest arms of any tyrannosaurid known, which were about twice as long as a tyrannosaurid of similar size. This is especially strange since Daspletosaurus is also known to have had really short legs, the shortest in the family, while most other tyrannosaurs had rather long legs for theropods. (I have a theory as to why this might have happened in Daspletosaurus, but I will talk about it farther down the post)

One of the most interesting things about tyrannosaurid arms though are the changes they experience as the animal grows. Young tyrannosaurs, and especially members of Tyrannosaurus itself, tend to have very long arms and claws compared to their parents; the size of a juvenile's arm was about the same length as the adult's arm, despite being 10 - 15 times less massive. Not just that, the arms of the juveniles have the same proportions as some allosaurids, and they aren't just long, but very strong and much more useful for grasping.

|

| Just try comparing the tiny stubs of Sue... |

|

| ...to the longer arms of Jane. |

The change in the arm lengths might reflect behavioral changes as tyrannosaurs grew, and also suggests that juveniles used their arms more than adults did. I have even heard some suggestions that the adult's tiny arms were there simply because of their juvenile stage. Although this idea may have some truth to it, I still think another theory for their function may be more likely.

___________________________________________________________________________________

The Function

So after that little overview on the forelimbs, let's try and see which of these theories is most logical:

Head over Hands:

|

| Why does Rex have three fingers? |

Of course, the first theory is that the arms were simply useless appendage that were lost as the skull grew to it's enormous size to keep it in balance. It's an interesting idea, but abelisaurids have tiny arms, even smaller than that tyrannosaurids' stumps, yet the skulls of these animals are actually smaller compared to body size than many large theropods. At the polar opposite, some carcharodontosaurids have skulls that are actually larger than most tyrannosaurs of similar size, and heads just as heavy. Yet they have typical three-fingered, long arms of most large theropods. With this logic, why didn't they lose their arms?

It's also interesting to note that theropod arms aren't very heavy in the first place, and shouldn't cause too much of a weight problem. So this theory doesn't really hold up very well. However, even if the head wasn't responsible for such a thing, it could be behavioral reasons that caused the arms to become reduced. The head was massive and built for crushing bone, which could have made the arms redundant simply because they didn't have a use anymore. This could also explain the abelisaurid arms, as the skulls of these animals were built for gripping, so the arms probably hadn't much use either.

However, as I explained earlier, even though they were small, the arms were heavily constructed and powerfully muscled. So no matter what people say, they were probably used for something. I will note, however, that their are many tyrannosaur specimens have been found with broken front limbs, injuries caused during life. A few specimens even show limbs that were nearly or completely torn off, but had healed over. The fact that we find these specimens survived losing these limbs suggests that these animals could go without using their tiny arms for extended periods of time, if not at all.

All for Love:

|

| Uhhhh, more three-fingered Rexes.... |

Some interesting theories suggest that the arms might have had some kind of mating purpose, either for grasping mates, as display organs (such behavior is seen in ostriches), or for keeping your mate happy by "scratching their itch."

The idea that they were used for grasping mates was first proposed by Henry Osborn (the one who described T-rex) in 1905, and has become one of the most popular theories for their use. I have to admit that I find much of the evidence stacking in this theory's favor. Being so big means that you have a harder time trying to mate. Tyrannosaurs were very large animals that primarily used their heads and jaws to secure a meal, thus the arms were mostly lost, but still kept to help right themselves when mounting a female.

I mentioned earlier that Daspletosaurus had the longest arms of any tyrannosaurid, but the shortest legs. This is consistent with the copulation theory. Since Daspletosaurus was so close to the ground, it would've had a much harder time grasping a mate during copulation. Thus, as the legs got shorter and the animal got closer to the ground, longer arms were probably favored to help with gripping onto mates.

The other two theories are also somewhat believable, but they are based on ideas with no evidence for. Nobody can test whether or not a female Gorgosaurus thought a male Gorgosaurus looked "sexier" with bright colorful armpits. Neither do we know weather or not Tarbosaurus really scratched their mates to make them feel better, or weather or not they were even social enough to exploit such behavior. They're all very interesting ideas, but they're nothing more; just ideas.

Prehistoric Forks:

|

| Ok, I will point out the numerous fingers, but I'm more worried about the feet... |

A rather odd theory that I've come across many times over the years is the idea that the tiny arms were used like a carving fork; holding onto the sides of a prey item as the jaws dispatched it and tore it apart. Other than the fact the arms had two sharp claws on them, their is basically nothing that suggests such a behavior, and the arm's design is not really built for it anyways.

For one, tyrannosaurid arms were very small and had a limited range of motion. This is the exact opposite of an animal that uses it's arms to grapple onto prey, such as the allosaurids and dromeosaurids, which have arms that are longer and have a large range of motion to reach out and pull another animal in towards it. They're built more like a carving fork, for holding onto something at close range that doesn't struggle, which brings more evidence to the copulation theory, as a mate is less likely to pull away than a prey item.

Another interesting point is the arm's overall length. They were so small that if a tyrannosaur was to grab onto a prey item, the animal would be literally pressed right up against the chest of the predator. Wouldn't you thing it'd be rather hard for something like a T-rex to dispatch a dinosaur that would basically be underneath it's body? Try eating something tied to your chest with just your mouth....

Also, note that evidence from the last few years have shown that tyrannosaurid hands faced inwards like all dinosaurs, not straight down like they were portrayed for so many years. Why do I point this out? Well one thing that you have to remember is that tyrannosaurs were often the largest animals in their local ecosystems. So if they were to try to catch something with their arms, wouldn't you expect the fingers to point downwards towards the smaller prey item? Not inwards which would've made it harder to hold on and grip.

Getting Up in the Morning:

|

| Hey, it's a picture of me in the morning... |

This is another rather interesting idea, that the arms were braces the were used to right the animal as it got up. This was first proposed in 1970 by Barney Newman, and became very popular at the time. During such activity, the forelimbs of the animal would have been extended in an action somewhat reminiscent of a push-up. However, with recent biomechanical analyses, such behavior seems impossible for a tyrannosaur to preform.

For one, as I mentioned above, the fingers weren't pointing downwards, they faced inwards. The shoulder joints were also too inflexible to allow the hand to face downwards, and prohibited a holding use for the claws to push on. This means that for the animal to be capable of pushing itself up, it would needed to do so with the sides of it's arms, and with very little surface area to actually push.

Even so, it doesn't seem too hard for a tyrannosaur to actually get up without the aid of it's arms. All you need to do is have your legs right underneath your center of mass, then it's just a mater of lifting yourself up. Think about modern day bipedal animals, like ostriches, which get up just fine without the aid of arms. Us humans can also easily get up from a crouching position without our arms. Unlike ostriches or humans though, Tyrannosaurs could have also used their tails to help right themselves through counterbalancing.

___________________________________________________________________________________

Conclusions

In my opinion, the only practical theory put forth so far is, ironically, the first to be proposed: copulation. It works well with what we know about large bodied animals, and these extinct tyrants seem to be no different. Although the arms may have been used for more than just copulation, I think that that was the only reason why they were retained for the last 20 million years of the Cretaceous. I find it interesting to think about what these animals would look like if they had survived past the extinction. Perhaps the giant Tyrannosaurs would keep their arms, but if smaller species evolved they may have lost them without any of the size restrictions.

But now here's an interesting little thought, note I said almost nothing in the post about whether or not the tiny arms suggest Tyrannosaurs were scavengers or a predators. That's because they don't indicate either. Many animals lack arms and are very efficient predators, such as Anacondas, Sharks, and Birds of Prey. So are many active scavengers, like Vultures and Piranha (despite popular media these are actually quite timid fish). Thus, it doesn't necessarily mean anything...

___________________________________________________________________________________

P.S. Sorry it has been so long since my last update. I've been busy with a science fair project at school and was unable to be on here at all. Luckily, I finished it earlier today and am hoping to make up for lost time with a special post about what I've been working on.

RaptorX